By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: July 23, 2015

From the looks of JPMorgan’s share price, one would think the financial world is bathing in a sea of tranquility rather than experiencing crashing commodity prices, tremors in the Eurozone, Canada acknowledging two quarters of contraction, ruptures in China’s stock markets, and energy and mining junk bonds losing 20 to 30 percent in a month.

JPMorgan’s share price hit an all-time closing high of $70.08 yesterday. The scary thing is, JPMorgan’s stock had a run from $32 to $42 just one month before Lehman Brothers blew up in 2008, marking the beginning of the biggest financial crash since the Great Depression; and there had been a year of financial warnings prior to that. (So much for global bank share prices being a bellwether on global financial stability.) Once the 2008 crash was clearly underway, JPMorgan shareholders saw 70 percent of their share price evaporate in a six-month stretch ending in March 2009.

JPMorgan is not some folksy community bank in New England with no counterparty exposure to other global banks or debt-ridden corporations. JPMorgan Chase is a global bank with over $2 trillion in assets “serving corporations and individuals in over 100 countries,” according to its web site.

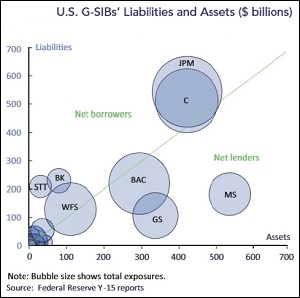

Graph from Office of Financial Research Report on Systemic Risks in U.S. Banking System (Symbols JPM and C denote JPMorgan and Citigroup, respectively.)

In February, the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Financial Research released a report showing staggering levels of interconnected risk among global banks. JPMorgan Chase had the highest overall score for systemic and interconnected risk.

The report was written by Meraj Allahrakha, Paul Glasserman, and H. Peyton Young and found that five U.S. banks had high contagion index values —JPMorgan, Citigroup, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, and Goldman Sachs.

The authors write:

“…the default of a bank with a higher connectivity index would have a greater impact on the rest of the banking system because its shortfall would spill over onto other financial institutions, creating a cascade that could lead to further defaults. High leverage, measured as the ratio of total assets to Tier 1 capital, tends to be associated with high financial connectivity and many of the largest institutions are high on both dimensions…The larger the bank, the greater the potential spillover if it defaults; the higher its leverage, the more prone it is to default under stress; and the greater its connectivity index, the greater is the share of the default that cascades onto the banking system. The product of these three factors provides an overall measure of the contagion risk that the bank poses for the financial system.”

Just this past Monday, the Federal Reserve announced that JPMorgan Chase faces a $12.5 billion shortfall in meeting the Fed’s 4.5 capital surcharge imposed on it because of its sprawling size and interconnectedness. That doesn’t seem like news that should send the bank’s stock to an all time high.

Things are now getting so tense on Wall Street that two investing icons, Carl Icahn and Larry Fink, had a war of words on stage at an investment conference last week. Here’s how the Wall Street Journal’s David Benoit tells what happened:

“ ‘BlackRock is an extremely dangerous company,’ Mr. Icahn proclaimed at CNBC’s Delivering Alpha conference in New York…Mr. Icahn steered the bulk of the conversation away from activism—the billing of the event—to his growing fears about a bubble in high-yield bonds and what he called dangers of exchange-traded funds [ETFs] run by firms like Mr. Fink’s.

“Mr. Icahn blamed the increasing prices for such relatively risky debt partly on Mr. Fink’s sprawling, $4 trillion asset manager and its exchange-traded funds, which Mr. Icahn said were causing a liquidity problem because they have snapped up so many assets…”

The fear is that there will be no buyers if investors in junk bond ETFs panic and stampede for the exits. Icahn is not the only person worrying about this scenario. In June, Richard Berner, Director of the Office of Financial Research, appeared at the Brookings Institution to discuss recent bouts of bond market illiquidity. Berner quoted SEC Commissioner Michael Piwowar on the issue of ETFs, who has said:

“The growth of bond mutual funds and exchange-traded funds in recent years means that these funds now hold a much higher fraction of the available stock of relatively less liquid assets than they did before the financial crisis…their growth heightens the potential for a forced sale in the underlying markets if some event were to trigger large volumes of redemptions.”

We may be closer to that trigger than many investors realize. Bloomberg Business is reporting this morning that “SandRidge Energy Inc. bonds have lost almost 30 percent since June, while notes of miner Cliffs Natural Resources Inc. are down more than 27 percent.” The article also notes that bonds of distressed debt issuers “are on pace to lose more than 20 percent for the second straight year, the worst performance since 2008.”