By Pam Martens: June 4, 2013

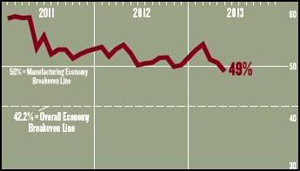

The Institute for Supply Management’s (ISM) manufacturing index contracted in May to a reading of 49, the lowest level since it registered a reading of 45.8 percent in June 2009. A reading below 50 means the manufacturing sector is contracting.

The data, called the PMI or Purchasing Managers’ Index, is based on a survey of more than 300 purchasing and supply executives from around the country who respond anonymously to a monthly questionnaire. With the exception of a four-year interruption during World War II, ISM has published the data monthly since 1931.

Both the index and a number of its individual components showed broad-based weakness in May. ISM’s new order index registered 48.8 percent in May, a decrease of 3.5 percentage points when compared to the April reading of 52.3 percent. The Backlog of Orders Index registered 48 percent, a 5 percent drop from the 53 percent reported in April. The New Export Orders Index registered 51 percent in May, which is 3 percentage points lower than the 54 percent reported in April.

None of this data is consistent with a raging U.S. stock market that is regularly setting new highs while a large swath of the global economy contracts. The data also removes the likelihood that the big worry last week – that the Federal Reserve might begin to taper back its monthly $85 billion purchases in the bond market – is a decidedly premature worry.

In his May 22, 2013 testimony to the Joint Economic Committee of Congress, Federal Reserve Chairman, Ben Bernanke, had this to say:

“Recognizing the drawbacks of persistently low rates, the FOMC actively seeks economic conditions consistent with sustainably higher interest rates. Unfortunately, withdrawing policy accommodation at this juncture would be highly unlikely to produce such conditions. A premature tightening of monetary policy could lead interest rates to rise temporarily but would also carry a substantial risk of slowing or ending the economic recovery and causing inflation to fall further. Such outcomes tend to be associated with extended periods of lower, not higher, interest rates, as well as poor returns on other assets. Moreover, renewed economic weakness would pose its own risks to financial stability.”

What Fed Chairman Bernanke is discussing in those 100 words is one word – deflation – his greatest fear. It’s the one outcome over which a central bank has zero control or monetary weapons for the simple reason that there is no level of interest rates low enough to stimulate spending and borrowing when the consumer believes prices will be cheaper if they simply wait. This is the lesson of the Great Depression, an area of scholarly research excelled in by Chairman Bernanke.

It is also the lesson of Japan, the world’s third largest economy behind the U.S. and China, which has been waging an unsuccessful battle against deflation for the past 15 years.

Japan’s Nikkei 225 stock index hit an all-time, intraday high of 38,915.87 on December 29, 1989. As the ravages of deflation took over, the Nikkei lost 82 percent of its value, closing at 7,054.98 on March 10, 2009. The Nikkei closed yesterday at 13,533.76, still almost two-thirds lower than two decades earlier.

On November 21, 2002, Bernanke, then a Governor of the Federal Reserve Board, delivered a speech before the National Economists Club in Washington, D.C. The speech was titled: Deflation: Making Sure “It” Doesn’t Happen Here.

Bernanke explained the difference between a deflationary recession and a normal recession as follows:

“…a deflationary recession may differ in one respect from ‘normal’ recessions in which the inflation rate is at least modestly positive: Deflation of sufficient magnitude may result in the nominal interest rate declining to zero or very close to zero. Once the nominal interest rate is at zero, no further downward adjustment in the rate can occur, since lenders generally will not accept a negative nominal interest rate when it is possible instead to hold cash. At this point, the nominal interest rate is said to have hit the ‘zero bound.’

“Deflation great enough to bring the nominal interest rate close to zero poses special problems for the economy and for policy. First, when the nominal interest rate has been reduced to zero, the real interest rate paid by borrowers equals the expected rate of deflation, however large that may be. To take what might seem like an extreme example (though in fact it occurred in the United States in the early 1930s), suppose that deflation is proceeding at a clip of 10 percent per year. Then someone who borrows for a year at a nominal interest rate of zero actually faces a 10 percent real cost of funds, as the loan must be repaid in dollars whose purchasing power is 10 percent greater than that of the dollars borrowed originally. In a period of sufficiently severe deflation, the real cost of borrowing becomes prohibitive. Capital investment, purchases of new homes, and other types of spending decline accordingly, worsening the economic downturn.”

Bernanke makes clear in his speech that deflation is triggered by a fall in aggregate demand. But what he never gets around to discussing is that in both the Great Depression and today, that fall in aggregate demand was accompanied by historic increases in wealth and income disparity among the population of the U.S. The bulk of consumers no longer had the ability to spend and prop up prices.

Today, according to studies done by Branko Milanovic, an economist at the World Bank’s Development Research Group, the U.S. has a higher level of income inequality than Europe, Canada, Australia and South Korea. The depth of the inequality is underscored by a study released last year by the National Bureau of Economic Research, showing that 50 percent of the U.S. population would not be able to come up with $2,000 within 30 days for an unexpected expense.

As of 2010, the top one percent of households owned 35.4 percent of all privately held wealth. The next 19 percent held 53.5 percent, leaving just 11 percent of the Nation’s wealth for the bottom 80 percent of the population.

Until wealth and income inequality in the U.S. is addressed, Fed Chairman Bernanke should continue to have sleepless nights about a nightmare deflation scenario.