By Pam Martens: December 20, 2012

It is close to five years since the Commodity Futures Trading Commission referred the Libor rate rigging matter to the U.S. Department of Justice. Yesterday was the first time the Justice Department brought a criminal charge in the matter – not against a U.S. bank where it would have a smoother road to prosecution, but against a Japanese subsidiary of the Swiss banking giant, UBS, and two of its former traders, Tom Hayes and Roger Darin.

The UBS subsidiary has received a deferred prosecution agreement, meaning it won’t be criminally prosecuted if it abides by the terms of the agreement, which includes not disputing the charges and continued cooperation. UBS paid global fines of $1.5 billion in the matter with the bulk of that money going to the U.S. Department of Justice. Hayes and Darin have been criminally charged in a complaint filed December 12, 2012 in Federal court in Manhattan. The complaint was unsealed yesterday.

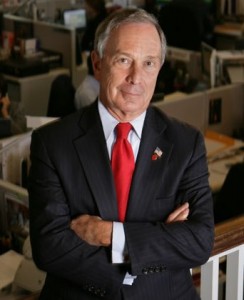

What the complaint makes clear is that it should not have taken five years to bring these charges. The traders effectively handed the Justice Department a slam dunk case by documenting each maneuver to rig the international interest rate benchmark known as Libor via instant messages recorded on a Bloomberg computer terminal. There were thousands of these messages over at least a five year period. Three questions arise: did Wall Street engage in a legal battle to prevent the release of these communications on the basis of trade secrets or proprietary/confidential trading communications; did the Bloomberg business empire, owned by Michael Bloomberg, the Mayor of New York City, immediately turn over the instant messages when requested to do so; why did traders feel their criminal messages would be protected on a Bloomberg computer terminal?

Every Wall Street firm regularly sends a loud and clear message to its workers that nothing you do on your work computers will be considered beyond the bounds of the firm’s prying eyes. Compliance departments at Wall Street firms are regularly required to monitor emails and other electronic communications for signs of illegal conduct. Every registered employee of a Wall Street firm who has read a business newspaper in the last four years also knows that the first thing a regulator will do in a fraud probe is to subpoena the emails.

And yet, sophisticated interest rate swap traders at the biggest banks in the world routinely engaged in rate fixing communications over a five year period and their established method of communication was over the Bloomberg terminal, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. Hayes communicated in this manner with colleagues at UBS, with inter-dealer brokers and with traders at other large Wall Street firms.

In an electronic chat on November 20, 2006, Hayes explained to a junior UBS employee that he and Darin “generally coordinate” and “skew the libors a bit.” Hayes further indicated that “really need high 6m fixes till thursday,” meaning he wanted the 6-month Libor rate submitted by UBS to be rigged higher to aid his trading positions until Thursday.

On August 15, 2007, according to the Justice Department, Hayes sent an electronic message to an inter-dealer broker noting that he needed “to keep 6m up till tues then let it collapse.” The broker responded: “doing a good job so far…as long as the liquidity remains poor we have a better chance of bullying the fix.”

In an electronic message on January 19, 2007, Hayes communicated the following to a trader at another Wall Street firm: “bit cheeky but if you know who sets your libors and you aren’t the other way I have some absolutely massive 3m fixes the next few days and would really appreciate a high 3m fix. Anytime i can return the favour let me know as the guys here are pretty accommodating to me.” The trader responded: “I will try my best.” Ten days later, the same trader sent an electronic communication to Hayes, asking: “Anything you need on libors today? High 6m would help me.” Hayes responded: “high 3m i’ll sort our 6m rate for you thanks.” Following the electronic chat, Hayes contacted a UBS colleague and requested a high 6-month Yen Libor submission.

According to the Justice Department, these Bloomberg communications continued through at least May 2010, after Hayes had left UBS and moved on to Citigroup. According to the complaint, Hayes left UBS and began working as a senior Yen swaps trader at Bank D [Citigroup] from approximately December 2009 through September 2010.

In a Bloomberg terminal electronic chat on May 12, 2010, while employed at Citigroup, Hayes stated to a trader at his former firm, UBS: “libors are going down tonight.” The UBS trader asked: “why you think so?” Hayes responded: “because i am going to put some pressure on people.”

As we reported on August 17 of this year in an article about Wall Street’s protection racket, “New York City’s Mayor, Michael Bloomberg, owes his billionaire status to Wall Street. There are currently an estimated 290,000 Bloomberg data terminals on Wall Street trading floors and offices around the globe, generating approximately $1500 in rental fees per terminal per month. That’s a cool $435 million a month or $5.2 billion a year, the cash cow of the Bloomberg businesses.”

Mayor Bloomberg was himself a former trader at Salomon Brothers. It would be good journalism and good business practices for the publishing side of the Mayor’s business empire, Bloomberg News, to share with the public the process through which these Bloomberg chat messages came into the possession of the Justice Department; just when that happened; and any efforts that were made by any party to prevent that from happening.

Citigroup, where there is documentation that Hayes continued his scheme, has yet to be charged in the matter.

See related articles:

Libor Scandal: The Unvarnished Story of Wall Street’s Heist of the Century

Libor Scandal Made Simple: It’s About Illegal Proprietary Trading