By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: July 5, 2019 ~

According to press reports around the globe, there’s going to be a hot confab this Sunday by the Board of Deutsche Bank that will focus on the potential to create a so-called “bad bank” to hold some of Deutsche’s toxic assets along with discussions of cutting 15,000 to 20,000 employees from the payroll – meaning as many as one out of every five employees could get the axe. A big part of the job losses will hit Manhattan where Deutsche Bank has a heavy presence on Wall Street — which it plans to severely pare back.

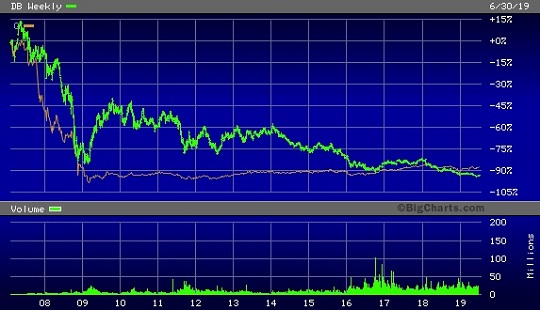

Here’s the short version on why the bank is contemplating these radical moves: Deutsche Bank has reported losses in three of the last four years; its share price has lost 90 percent of its value since February of 2007; as of the close of trading on Wednesday, Deutsche had $16.14 billion in common equity value versus $49 trillion notional (face amount) in derivatives; it’s had four different CEOs in just over four years; it can’t find a merger partner; and its home country of Germany, unlike the “throw money at the Wall Street mega banks” U.S. government, doesn’t seem inclined to hand a life line to Deutsche Bank’s sinking hulk.

To wrap your mind around the concept of a “bad bank,” let’s look at what Citigroup did in January 2009. After turning its former CEO, Sandy Weill, into a billionaire from obscene stock option grants and paying former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin over $120 million over a decade for a seat on its Board, and other similar drunken sailor compensation sprees, accounting tricks and a toxic derivatives book, Citigroup found itself teetering during the 2008 financial crisis. The U.S. government infused $45 billion in equity capital into its sinking carcass but its share price continued to collapse. Fellow banks on Wall Street refused to lend to it.

So after reporting more giant losses for the fourth quarter of 2008, on January 16, 2009 Citigroup announced it was gathering up all of its toxic assets and shoving them into a “bad bank,” to be called Citi Holdings. The bad bank would also hold the amorphous $301 billion in assets that the U.S. government had agreed to backstop against future losses the prior November.

The day that Citigroup made its bad bank announcement, Friday, January 16, 2009, its stock closed at $3.50 a share. By March, it had lost two-thirds more of its value.

Today, after performing a 1-for-10 reverse split on May 9, 2011 (leaving shareholders with 1 share for each 10 shares previously held) Citigroup’s share price is still down 86 percent from where it traded in early 2007, before the financial crisis. And that’s not the worst part of this story.

In addition to the government guarantee on over $300 billion in assets, a $45 billion government equity capital infusion, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation also guaranteed $5.75 billion of Citigroup’s senior unsecured debt and $26 billion of its commercial paper and interbank deposits. And while all of these serial bailouts of Citigroup were going on by various Federal government agencies like the U.S. Treasury and FDIC, the U.S. central bank, the Federal Reserve, was secretly funneling a cumulative $2.5 trillion in revolving loans to Citigroup, much of which had interest rates below 1 percent while Citigroup continued to charge its credit card customers who were struggling to survive an economic crisis that it and its fellow mega banks on Wall Street had created, high double-digit interest rates.

The Fed’s secret loans to Citigroup lasted from December 2007 to at least July 2010. The public finally learned about the loans from a Government Accountability Office (GAO) audit in 2011. The demand for the audit had been tacked onto legislation by Senator Bernie Sanders. The Fed fought to keep these loans secret by waging a multi-year court battle with the U.S. media.

According to the Financial Times, Deutsche Bank is thinking of moving upwards of $56 billion in long-dated derivative contracts into its bad bank. Frankly, that seems like a drop in the bucket. And, we’ve heard nothing thus far about any white knight equity infusions on the horizon and nothing about any potential government assistance from Germany. So exactly how does this bad bank make sense?

The ideal bad bank is one that houses toxic assets that the bank can sell off over time as buyers emerge while isolating the good, productive assets in the “good bank.” But exactly who wants to buy long-dated derivatives from Deutsche Bank except at possibly steeply discounted prices, which would mean taking more losses without any apparent government support.

Wall Street banks and the Federal Reserve have good reason to be worried about whether Deutsche Bank’s restructuring plans succeed. Deutsche Bank’s $49 trillion in notional derivative tentacles extend into the mega Wall Street banks. According to a 2016 report from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Deutsche Bank is heavily interconnected financially to JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and Bank of America as well as other global banks in Europe. In its in-depth report, the IMF concluded that “Among the G-SIBs, Deutsche Bank appears to be the most important net contributor to systemic risks, followed by HSBC and Credit Suisse.”

The U.S. taxpayer has even more reason to be outraged that a serially-charged German bank could potentially cause waves in the U.S. financial system. That’s because Deutsche Bank was previously on the receiving end of obscene bailout funds from the U.S. government. When the government bailed out the giant insurer, AIG, in 2008, a good chunk of that money went out the back door to make Deutsche Bank whole on its derivative bets and other dealing with AIG. Deutsche received $2.6 billion in collateral postings for derivatives; another $2.8 billion from Maiden Lane III (a creation of the New York Fed to buy up Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) from AIG); and a whopping $6.4 billion under securities lending agreements Deutsche Bank had with AIG.

In addition, according to the GAO audit report, Deutsche Bank received $354 billion in low-cost revolving loans from the U.S. Federal Reserve during the same period that Citigroup was drinking at the trough. (See After a $354 Billion U.S. Bailout, Germany’s Deutsche Bank Still Has $49 Trillion in Derivatives.)

U.S. regulators should be all over this situation with Deutsche Bank. Instead, just like in the leadup to the 2008 financial collapse, regulators have decided it’s safer for their career prospects on Wall Street to plant their heads firmly in the sand.