By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: October 21, 2020 ~

Turns out the federal government’s plan for dealing with a mega bank failure on Wall Street is no better conceived than the federal government’s plan for dealing with the worst pandemic since 1918.

The Federal Reserve issued two press releases yesterday about “large banks.” One read: “Agencies finalize rule to reduce the impact of large bank failures.” The other read: “Agencies issue final rule to strengthen resilience of large banks.”

Wait. What? Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has been telling anyone who would listen this year – from Congress to viewers of the Today show – that the large banks have been a “source of strength” during the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. If that were true (which we’ve questioned from the first time Powell said it) why is the Fed now worrying about a “large bank failure” and the need to “strengthen” large banks?

The first press release from the Fed yesterday deals with the fact that the biggest banks on Wall Street remain interconnected to one another. If you recall, in 2008 the interconnections of Lehman Brothers, Citigroup and AIG to the biggest banks on Wall Street created a daisy chain of rapid meltdowns across Wall Street.

So federal regulators had this plan: They would make the largest banks issue TLAC debt – “Total Loss Absorbing Capacity” debt. The idea, according to the regulators, was that this “debt could be used to recapitalize the holding company during bankruptcy or resolution if it were to fail,” rather than putting the taxpayer on the hook for another massive bailout like 2008.

Now, if you read between the lines of the finalized rule, it would appear that the banks have attempted to game this plan by buying up their own and/or each other’s TLAC debt, thus increasing the very interconnectedness and systemic risk that the federal regulators were trying to avoid. So the federal regulators, including the Fed, are going to spank the large banks by penalizing them on what they will count toward their regulatory capital if they hold their own or other bank’s TLAC debt.

The problem is that the largest interconnected risk between the banks is not their mutual holdings of each other’s debt, which is in the billions of dollars, but their mutual holdings of each other’s derivatives, which are in the trillions of dollars, in terms of face amount. The tangle of incestuous derivative relationships is as bad, if not worse, than it was in 2008. And these trillions of dollars in derivatives, thanks to a repeal of a part of Dodd-Frank through lobbying by Citigroup, are still sitting at the federally-insured part of the Wall Street bank, where the taxpayer is still on the hook for any blowup.

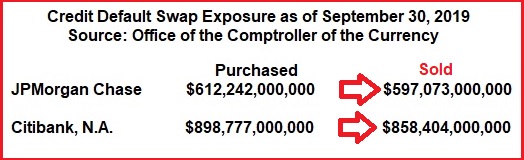

Credit default swaps, which allow Wall Street banks to buy and sell bets on which banks or corporations will blow up in a crisis, played a major role in the 2008 financial collapse. Despite that, according to the September 30, 2019 report from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), JPMorgan Chase has exposure to $1.2 trillion in Credit Default Swaps while Citibank has exposure to $1.76 trillion. According to the same OCC report, the total exposure to Credit Default Swaps among all national banks in the U.S. is $3.7 trillion – meaning that just these two banks are responsible for 80 percent of that exposure.

Who is on the other side of these trades, i.e., the counterparty? No one really knows because these are mostly private contracts between two parties. That was supposed to change under Dodd-Frank, where the derivatives would become centrally-cleared or traded on exchanges, but the majority of derivatives remain over-the-counter private contracts.

Phil Angelides was the Chair of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission that investigated the causes of the 2008 crash. On June 30, 2010, he had this to say at a hearing convened specifically to examine “The Role of Derivatives in the Financial Crisis.”

“I must say that despite 30 years in housing, finance, and investment — in both the public and private sectors — I had little appreciation of the tremendous leverage, risk, and speculation that was growing in the dark world of derivatives. Neither, apparently, did the captains of finance nor our leaders in Washington.

“The sheer size of the derivatives market is as stunning as its growth. The notional value of over the-counter derivatives grew from $88 trillion in 1999 to $684 trillion in 2008. That’s more than ten times the size of the Gross Domestic Product of all nations. Credit derivatives grew from less than a trillion dollars at the beginning of this decade to a peak of $58 trillion in 2007. These derivatives multiplied throughout our financial markets, unseen and unregulated. As I’ve explored this world, I feel like I have walked into a bank, opened a door, and seen a casino as big as New York, New York. Unlike Claude Rains in Casablanca we should be ‘shocked, shocked’ that gambling is going on.

“As the financial crisis came to a head in the fall of 2008, no one knew what kind of derivative related liabilities the other guys had. Our free markets work when participants have good information. When clarity mattered most, Wall Street and Washington were flying blind…”

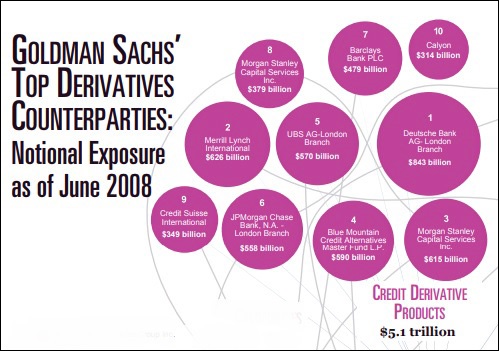

We’re still flying blind. For an idea of how the mega banks on Wall Street game the system, take a look at the graph below showing the counterparties to Goldman Sachs’ derivatives in 2008. Pay attention to the fact that three of the counterparties to Goldman – JPMorgan Chase, UBS, and Deutsche Bank – are using their London branches, thus making transparency impossible for U.S. regulators. Does any sensible person believe that’s not happening today?

Under the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010, the Office of Financial Research (OFR) was created to provide timely warnings of systemic risk to federal regulators of banks. OFR researchers, Jill Cetina, Mark Paddrik, and Sriram Rajan, released a study in 2016 showing that, in their opinion, the Fed’s stress test that measures derivatives counterparty risk on a bank by bank basis is all wrong. The problem, according to the researchers, is not what would happen if the largest counterparty to a specific bank failed but what would happen if that counterparty happened to be the counterparty to other systemically important Wall Street banks. (Think Lehman Brothers, Citigroup and AIG in 2008.)

Cetina, Paddrik, and Rajan wrote that the Fed’s stress test “looks exclusively at the direct loss concentration risk, and does not consider the ramifications of indirect losses that may come through a shared counterparty, who is systemically important.” By focusing on “bank-level solvency” instead of the system as a whole, the Fed may be ignoring the real problem of systemic risks in the system. The researchers explained further:

“A BHC [bank holding company] may be able to manage the failure of its largest counterparty when other BHCs do not concurrently realize losses from the same counterparty’s failure. However, when a shared counterparty fails, banks may experience additional stress. The financial system is much more concentrated to (and firms’ risk management is less prepared for) the failure of the system’s largest counterparty. Thus, the impact of a material counterparty’s failure could affect the core banking system in a manner that CCAR [one of the Fed’s stress tests] may not fully capture.”

What does it say about our federal regulatory structure when the same dangers that blew up the U.S. financial system, the U.S. economy and the U.S. housing market in 2008 are still with us today? What does it say about who is really in control of Congress? (See Meet Your Newest Legislator: Citigroup.)

As for the second press release issued by the Fed yesterday, it turns out that the Fed is not really trying to “strengthen resilience of large banks” but is going to further degrade the safeguards. According to Fed Governor Lael Brainard, who cast a dissenting vote, the finalized rule will dramatically reduce the liquidity held by the largest banks – liquidity that would support them in the case of a run on the bank. You can read her full statement here.

If you need further convincing that the Fed has been fully captured by the mega banks on Wall Street, read our more than 100 articles since March on that topic at this specially created archive.